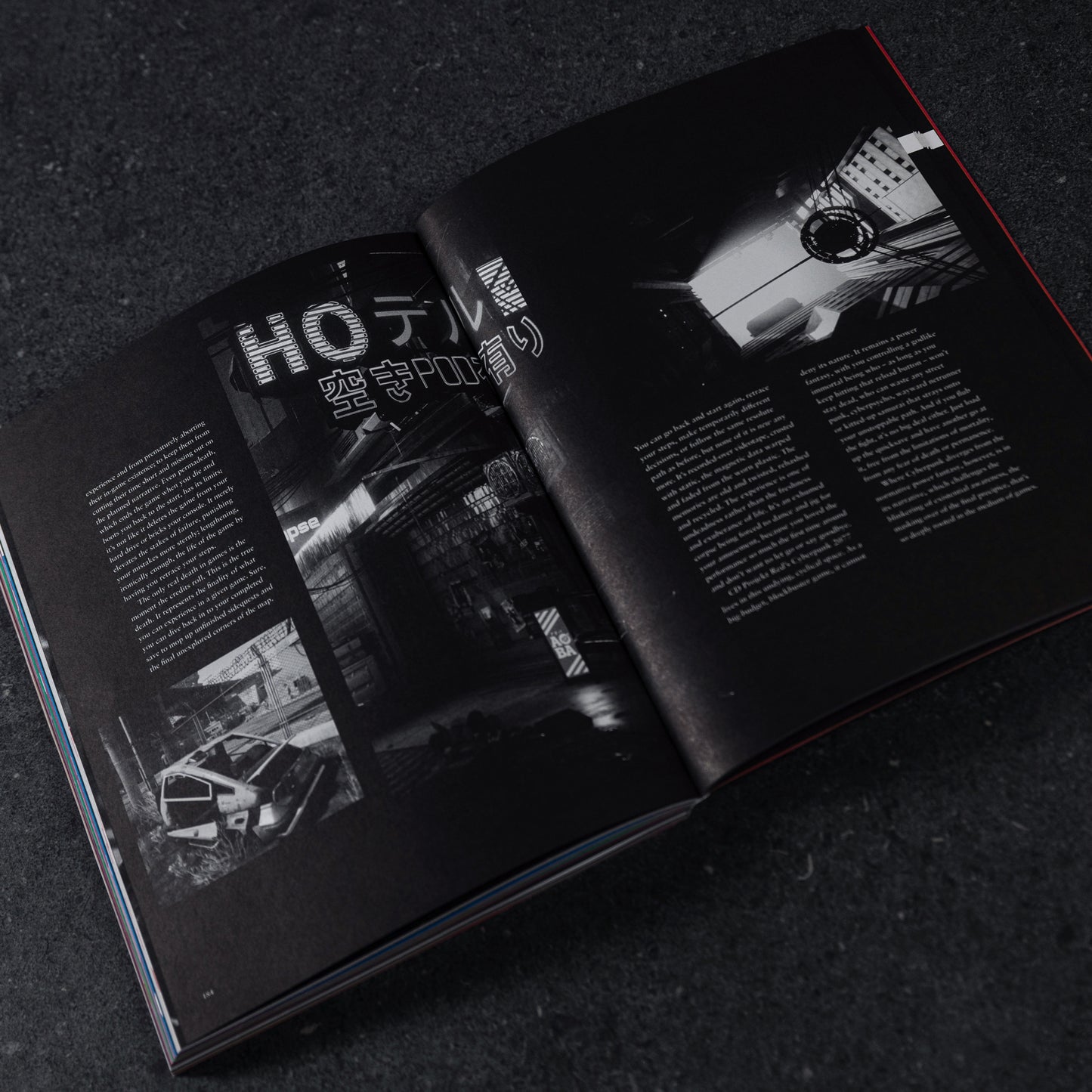

Yussef Cole ON life, death and Cyberpunk 2077

Interview with Yussef Cole

Yussef was born in the Bronx, New York. He studied film and literature, and now works as a designer and broadcast animator. He and his team won an Emmy award for Netflix’s Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj in 2019. He is also a freelance games critic, writing essays that analyse games in a socio-political and emotional context. His work has appeared in The New York Times, Wired, Paste, Polygon, Unwinnable and Vice.

Yussef cole ON life, death and Cyberpunk 2077 in ON: Volume One.

You start your piece by talking about how games often present the perfect conditions to protect "against the rushing river of time." When did you start to notice this quality of them, and what do you think makes them so suited to this?

Yussef Cole: Good question. I think it's really been the rise of live service games, which I talk about later in the piece. Fortnite broke the door wide open for this type of game, but it feels like it's taken over mainstream gaming: the expectation of games as platforms that extend infinitely into the future, rather than discrete, limited experiences. Maybe it's the ability to constantly download patches and enlarge a game until it's filled your hard drive like a cancer that's made the most difference. Before, when the game was on a disc, that was all you were going to get, and you were satisfied with that. But I do think it's a tendency that's always been part of games. I remember talking to a bartender once who was big into Dark Souls and said he just kept playing consecutive New Game modes until he was a dozen or so playthroughs in. Which to me is just the perfect depiction of some kind of eternal purgatory that only games can provide. Since they're interactive there are usually enough variations in the experience that you don't feel like you're doing the exact same thing over and over again (like you would watching a movie or reading a book). You can basically live in this world and because it's code on a disc, it isn't going anywhere.

You write that in many ways Cyberpunk has to treat death the way other games do - you can reload quicksaves when things go wrong. And yet it goes much further in its consideration of death. How does it do this?

Yussef Cole: To be a modern game you have to give allowances to the player. You have to be played, and you have to be completable. And cyberpunk is, in most ways, a big budget modern game that has to cater to a huge audience. But, as in all games, finishing the story represents the actual end of the character, since you can't take any more actions with that character. Most games kind of ignore this or give you a happy ending. Cyberpunk really writes the functional reality into the texture of its story. Your character is dying in the game and finishing it means letting them go in a real way. Your character is given the option to struggle; to hold on to eternity and live on but those endings still wrestle with what it means to hold on to life at the cost of meaning. Living for its own sake is ultimately unsatisfying. The game leads us in the direction of making our death mean something, going out in a blaze, rather than cowering and hiding and living in a compromised way.

One of the most striking points you make is that games about death - art and literature about death - are almost always about life, too. How do you think games best capture this sense, and apologies for my clumsy wording, that the knowledge of death can make life richer?

Yussef Cole: Games give us the chance to die, without really dying. So they give us an, albeit terribly limited, model with which to explore what it means to have limits; what to do within those limits. Most of the time we're kind of struggling against those limits, like we do in life. But certain games, Cyberpunk among them, challenge the promise of endless ambition. They allow us the opportunity to reckon with the fact that no matter how hard we strive, no matter how big we make ourselves, we will always run up against some kind of barrier, something that cuts our ambition off short. So then it becomes about how we spend the time we have. It becomes about how we can make peace with the limitations of the experience. To grow up and learn to walk away, rather than sink deeper in and live forever in the fantasy.

Read the full feature in ON: Volume One:

ON: Volume One