Jeremy Peel ON the history of videogames via Wolfenstein

Interview with Jeremy Peel

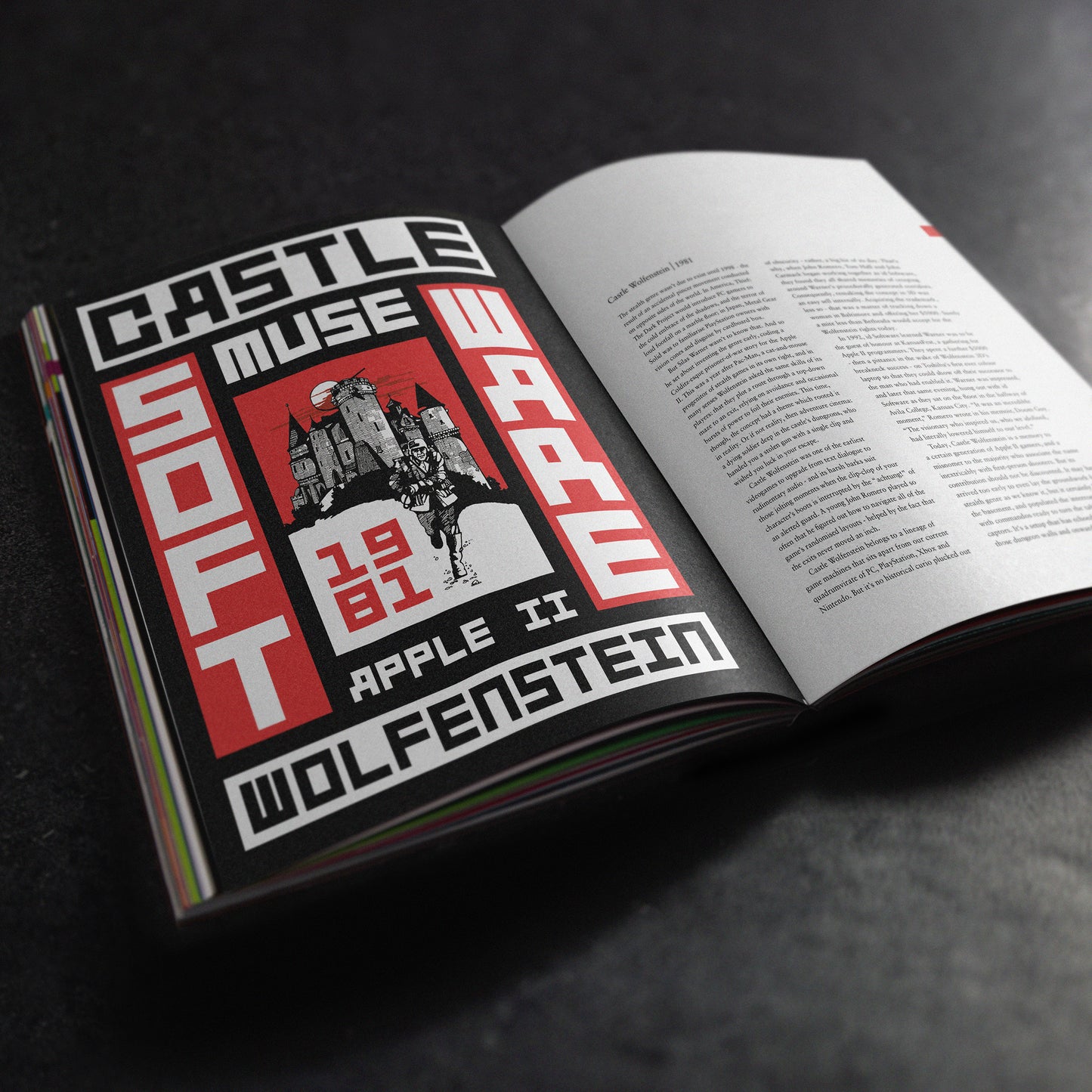

Few series have been reinvented as many times as Wolfenstein. More than once, it’s led the industry. And when it hasn’t, it’s acted as a mirror - reflecting the damaging design and production trends of triple-A. Going all the way back to 1981 and Escape from Castle Wolfenstein, Jeremy Peel tells the story of a truly classic series that was always ahead of the curve and explores how it's helped to shape the wider world of games, one new idea at a time.

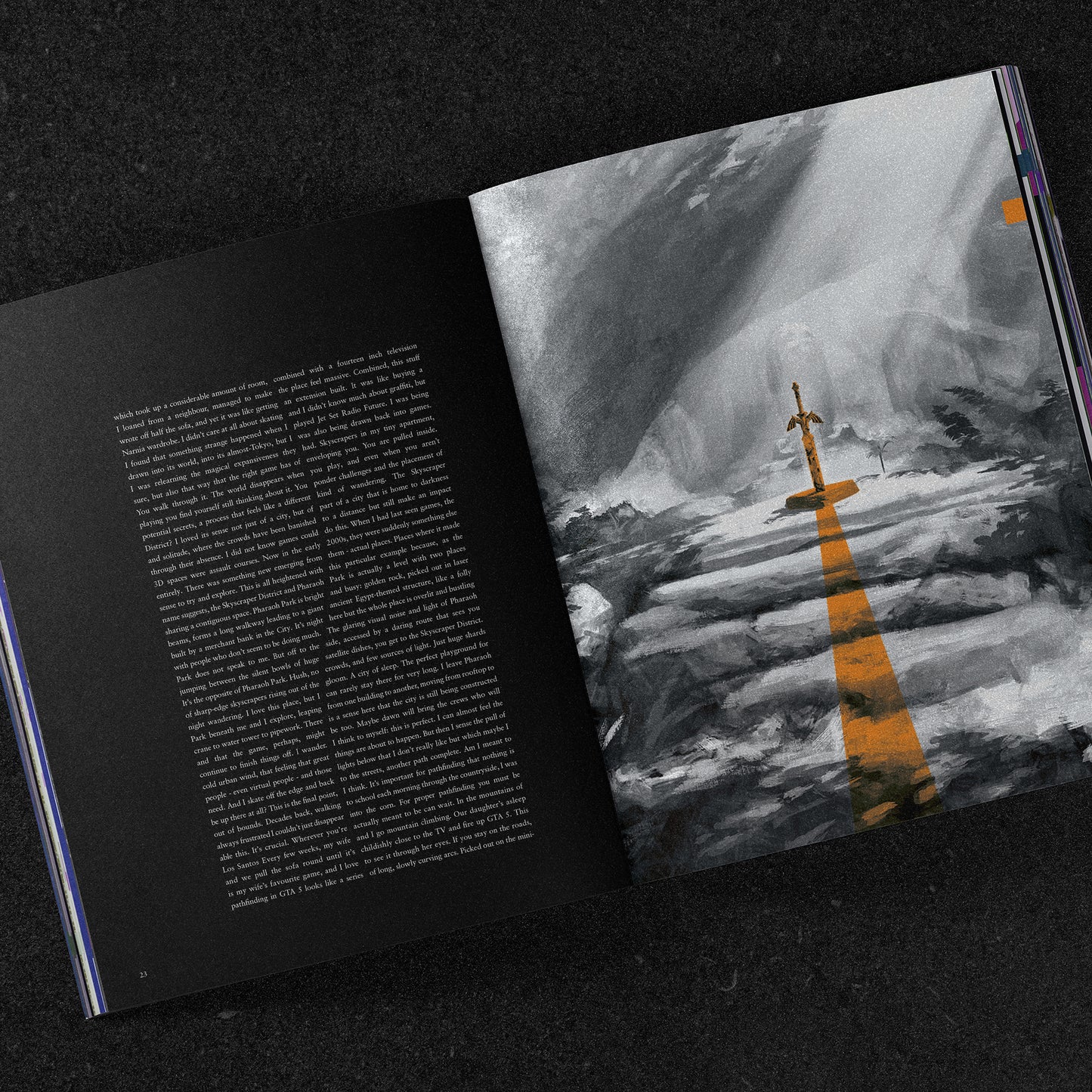

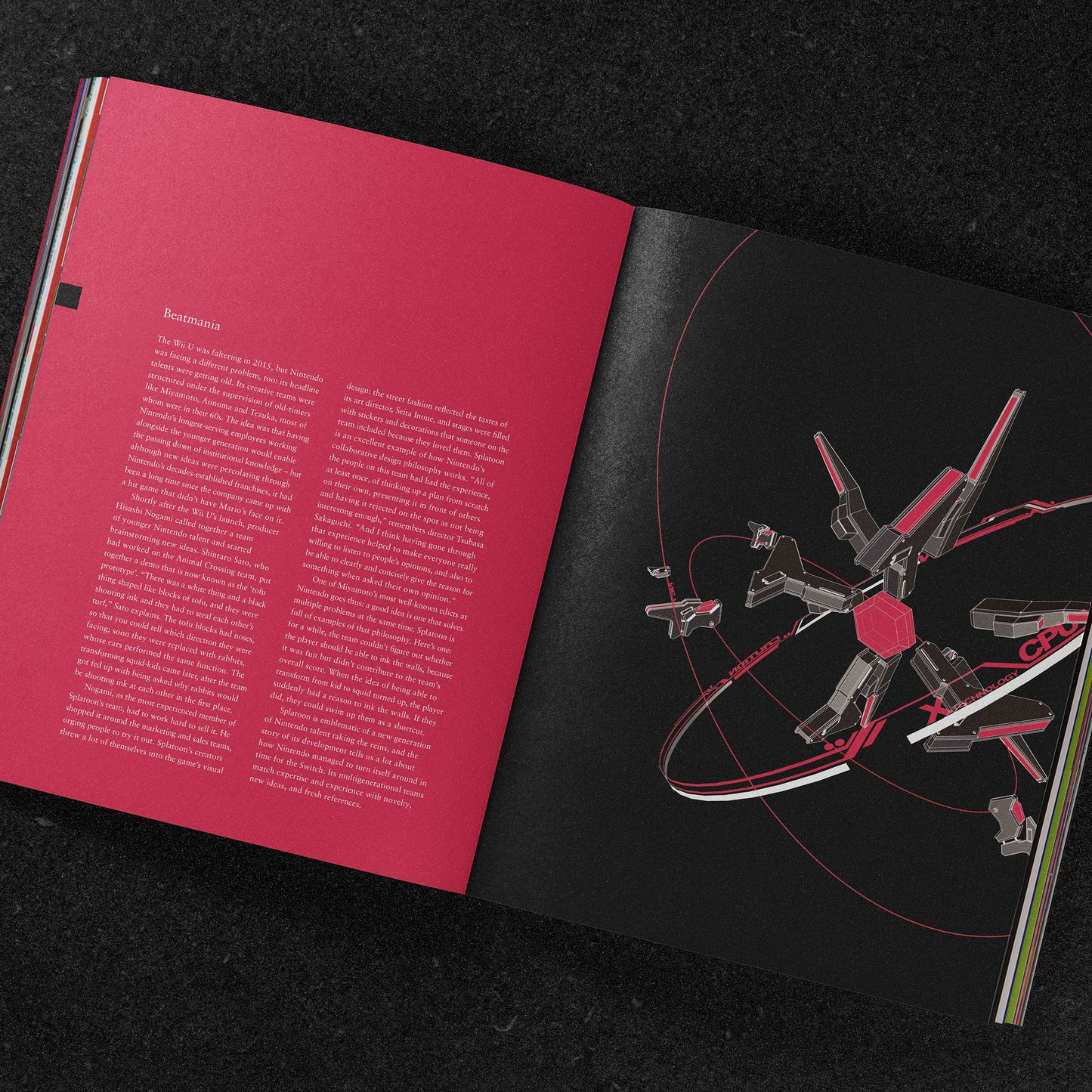

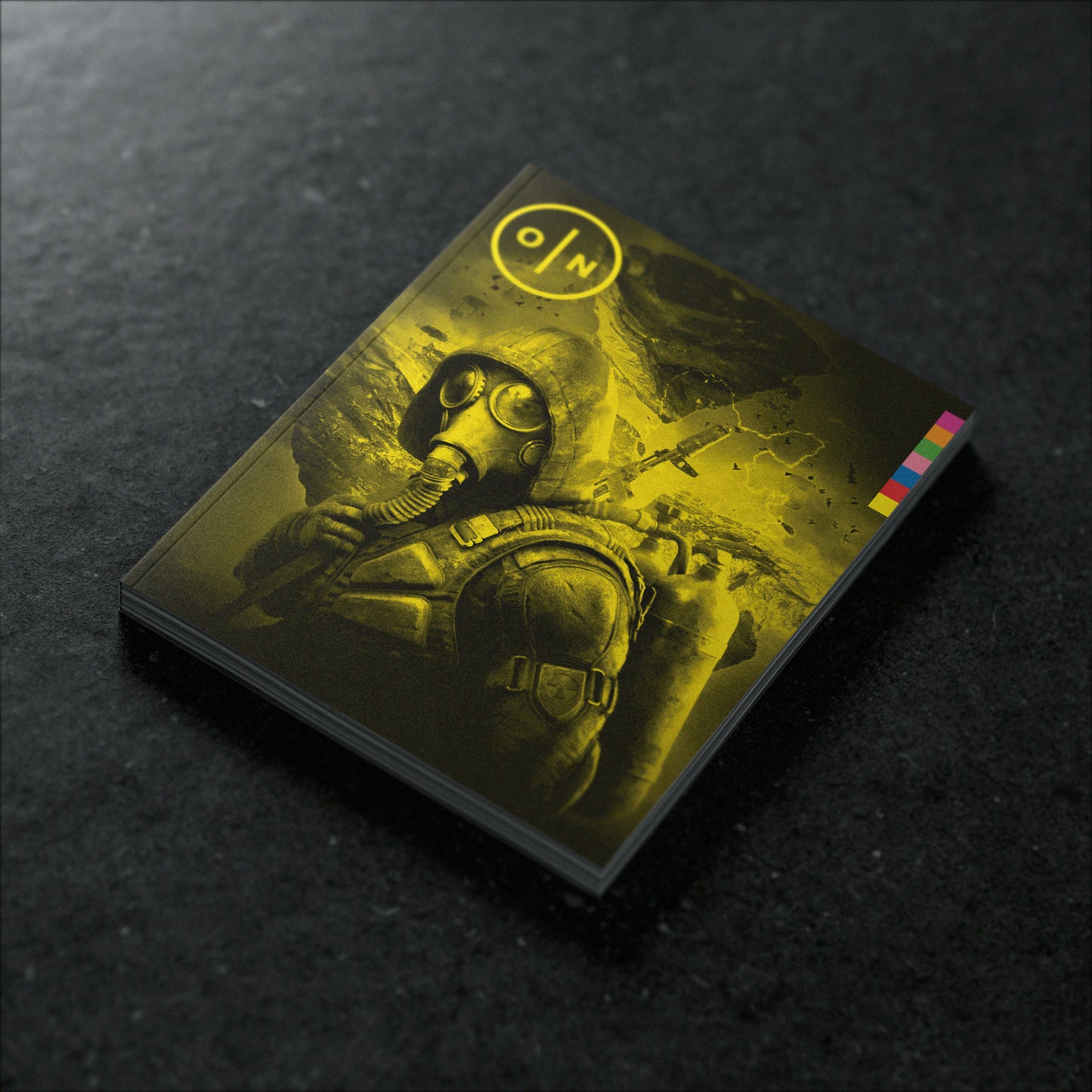

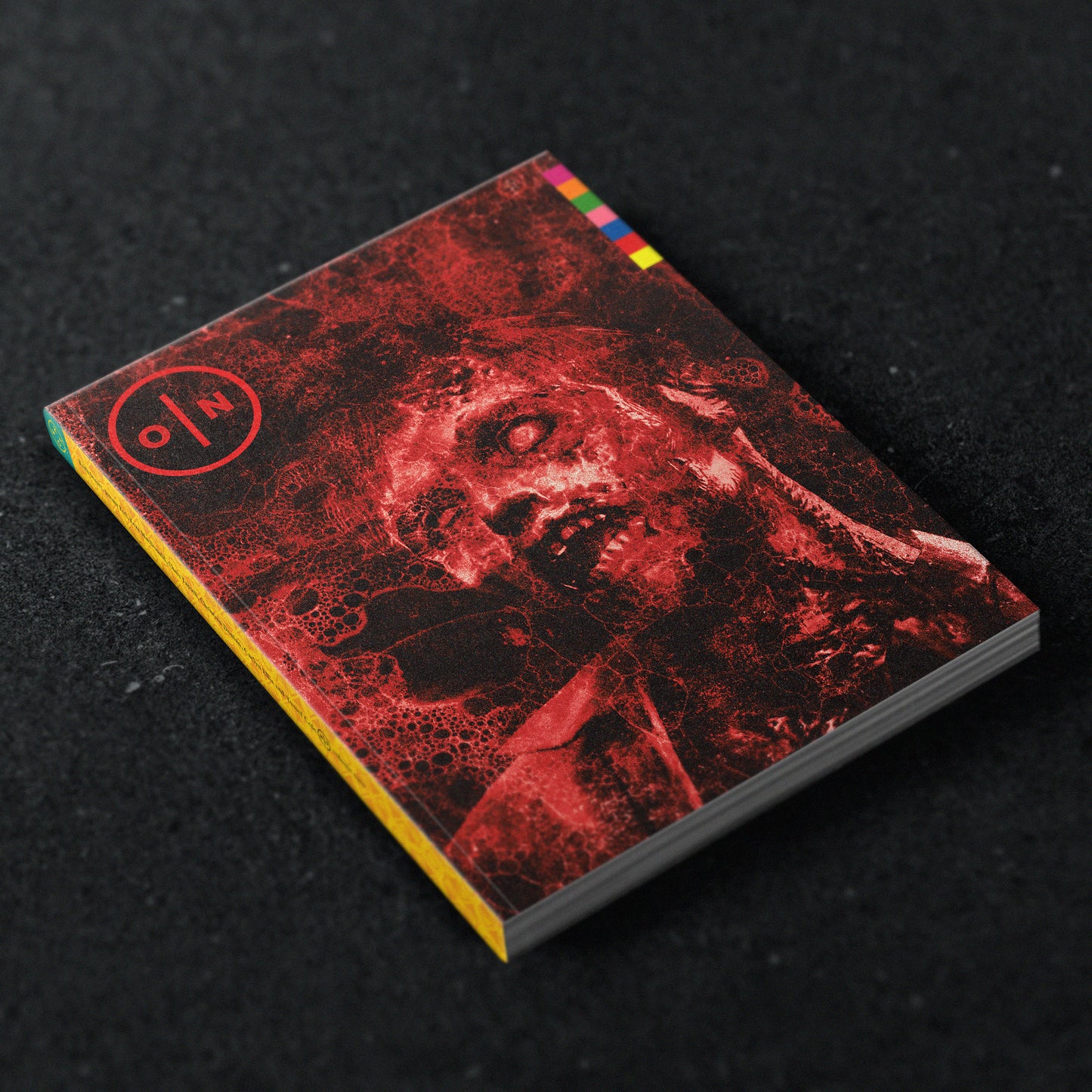

Jeremy ON the history of videogames via Wolfenstein in ON: Volume Two.

I get the impression that the Wolfenstein games are heavily plaited together with your idea of what a videogame is a lot of the time? Is that fair?

Jeremy Peel: I grew up with Thief, Deus Ex and Command & Conquer as my lodestars. Aside from giving me a keen appreciation for the £5 budget games section at ASDA, I suppose these games also gave me a love for first-person immersion, dense atmosphere and alt-history worldbuilding. Which is what the Wolfenstein games combine, coming together in one big mighty Mecha-something. Not Mecha-Hitler. Mecha-anyone-else.

When did you first realise that these games were special?

Jeremy Peel: Not for ages, really. I remember seeing a friend playing Return to Castle Wolfenstein, which looked like a proper horror game, and thinking, ‘oo err, not for me, thanks’. Then MachineGames came into the picture and embraced the concept of first-person cinema that Call of Duty had invented. Unlike COD, they had female characters, and tense Tarantino-esque showdowns on train tables. Even more tense than when someone’s already taken up the space for a laptop on the 9:15 from Sheffield to London.

Why do you think these games have not just survived but remained so relevant in terms of videogame design and trends?

Jeremy Peel: Wolfenstein’s capacity for reinvention is pretty extraordinary. That’s partly because it’s capable of a range of tones, I think - B-movie brainlessness, classical Hollywood derring-do, warped-mirror commentary on the ills of society. Even romance, as MachineGames has proven.

But I think there are lots of deserving old games that don’t get remixed in this way. Wolfenstein gets this treatment because it was the starting point of the first-person shooter. It holds a hallowed spot in games history, and thus attracts some very special developers to work on it.

In some ways, I’m even more interested when Wolfenstein doesn’t remain relevant and appears to fall slightly behind the curve. Because that can tell us a lot about the growing pains of the games industry. It’s one thing I wanted to dig into with the ON article.

If you were recommending the series to someone, which game would you recommend and why?

Jeremy Peel: It would have to be Wolfenstein: The New Order - which is the moment when MachineGames somehow remodelled the series as a vehicle for prestige storytelling, without sacrificing its goofiness or straightforwardly entertaining shootouts. The softly-spoken BJ Blazkowicz of The New Order is a poet in his head and a dancer on the battlefield. And around him is a brilliant ensemble cast that grows into a found family as the series rolls on. It’s so much more than anyone had a right to expect from a game about a gun glued to a camera.

Read the full feature in ON: Volume Two:

ON: Volume Two